Click here to access all three parts of the Hokie Defense series by Raleigh Hokie

We all have heard the terms. It is nearly impossible to watch a football game on television without hearing the analyst mention “cover two” or “cover three” or “zone blitz” multiple times. Most post-game analysis articles that I have written over the years have referenced many of those terms as well.

What are they and what do they mean?

This final segment on the Virginia Tech defense will focus on the more popular pass coverages used by the Hokies, as well as other college and professional defenses. There are dozens of variations that teams use to disguise and confuse offenses, so the focus here will be on the basic types of pass coverage utilized by most defenses today.

Let’s get to it.

Is it Man or is it Zone?

Pass coverages can be broken into one of two primary categories:

- Man-to-Man coverage

- Zone coverage

Man-to-man is the most obvious coverage technique and the easiest to understand. Just as it sounds, man-to-man coverage is the match-up of a single defender against each of the five eligible offensive receivers. In man-to-man coverage, each defender is responsible for covering his receiver all over the field regardless of where the receiver goes.

Man-to-man is the most obvious coverage technique and the easiest to understand. Just as it sounds, man-to-man coverage is the match-up of a single defender against each of the five eligible offensive receivers. In man-to-man coverage, each defender is responsible for covering his receiver all over the field regardless of where the receiver goes.

Man-to-man is the most intuitive coverage for players to learn and it is the easiest for coaches to teach in terms of assignments. But it is also the riskiest type of coverage because it can be difficult for defenders to stay with receivers as they make their breaks and cuts through the route.

Zone coverageis the concept of defenders covering a specific area of the field, picking up and releasing receivers as they move into and out of that designated area. There are many different types of zone coverages, but they are all based on the premise of covering an area of the field vs. a specific receiver.

Zones are more complex than man-to-man and it takes time for players to learn the subtleties of each type of zone coverage. In all zones, the players have to work in-sync with each other and each defender has to be cognizant of the routes of multiple receivers such that they can adjust their zone responsibilities to prevent the overflow of a zone in another area. This is called “pattern read” and it is a very important aspect of all zone coverages.

Offenses look to “flood” specific zones with multiple receivers with the hope that the defender responsible for that area will have to make an either/or decision as to which receiver to cover. With “pattern read”, multiple defenders adjust their zone responsibilities based on the collective routes of the receivers in order to prevent an overflow of multiple receivers against a single defender.

When played properly, zones reduce the risk of big plays in the passing game. Multiple zone coverage options offer the chance for defenses to disguise the specific coverage that is called, which makes it very difficult for quarterbacks to get a good pre-snap read on what the defense is doing. A defense can easily show a man-to-man coverage look when in fact the coverage is one of several zone coverages. This can be very confusing to a QB that is trying to determine the coverage before he takes the snap. And disguising coverages and confusing the QB is the first step to having a strong pass defense.

As we covered in Part 2 of the series, Tech’s base pre-snap defense is a 4-3-4 set with two high safeties. The move to this 2-high safety base in 2004 allowed the Hokies to get to multiple man-to-man and zone coverages from the same pre-snap base set. This not only made it easier for the defense to disguise the actual coverage, but it was easier to disguise pressure as well. Offenses could no longer isolate match-ups, nor could they read where the pressure was coming from or when it was coming.

While these adjustments had significant impact on the ability to defend the pass, the defense just couldn’t sit back in 2-deep sets (with seven-in-the-box) all the time because that would expose them in the run game. Remember, the top priority for a Bud Foster defense is to stop the run. Period. Sitting back in 2-deep zones is not going to get that done consistently. The key was to remain aggressive, use different pressure concepts to keep the offense guessing, and disguise the pass coverage from the same 2-high safety pre-snap base.

Pressure Concepts

Pressures can be broken into two basic categories – run blitzes and pass blitzes. Technically, a blitz is terminology for maximum pressure, but for the purposes of this article, I will interchange the terms “pressures” and “blitzes” as being one in the same.

Run blitzes are geared to defend the run game by having players aggressively attack different gaps (versus reading the play and reacting from there). This creates an aggressive approach to run defense and it makes the blocking angles more difficult for the offense. From the seats, run blitzes look like any other blitz, but the objective is to immediately secure run gaps rather than get to the QB. Run blitzes are an important ingredient in run defense from a 2-high safety base. They allow the Hokies to have a solid run/pass balance in base defense while still being aggressive in stopping the run – the #1 priority of Bud Foster’s defensive scheme.

Pass blitzes can be subdivided into two types – man pressures and zone pressures. Man pressures are the “old fashioned” type of blitzes where the defense sends extra players to get the QB while matching up with the receivers in man-to-man coverage. Zone pressures are a more modern concept and involve sending extra defenders at the QB while playing some form of zone coverage down the field. This allows the defense to remain aggressive, but with less risk.

Pressure and Pass Coverage ….. How They Relate

Anyone who has watched Virginia Tech over the years knows that Bud Foster likes an aggressive, pressure-style of defense. Out of the old 8-man fronts, the Hokies would blitz on nearly every play. Now, with the 2-high safety base, the blitzes are varied, directional and more orchestrated.

Ok, so what does that mean? Blitzing used to be more of an all-out nature – match-up one on one against each eligible receiver and send everyone else to the QB. That usually resulted in a lot of sacks and negative yardage plays, but occasionally it resulted in big plays for the offense. The evolution of offensive concepts such as the quick passing game and maximum protection schemes neutralized the effects of all-out blitzing and increased the likelihood of big plays for the offense. Adjustments were needed and the concepts of pressure had to evolve as well.

The Hokies will still “bring the house” in certain situations or against certain formations (e.g., an empty backfield), but more often than not, the pressure philosophy is tied to a number of other factors, including offensive personnel, formation, tendencies and the type of pass coverage called for that play.

Much of this goes hand in hand with the adjustments that were made to better defend the spread-type offenses that were having success against the 8-man front schemes. We have covered the adjustments to player alignment and responsibilities and the move to the 2-deep safety base. But the adjustments also included pressure techniques and pass coverages.

When it comes to breaking down film, no coaching staff does it better or more thoroughly than Bud Foster and his defensive assistants. Through extensive film study each week, Coach Foster and his staff are able to breakdown offensive tendencies for every personnel group, formation, and down/distance situation. Armed with that information at game time, Foster will make the defensive call for each play based on what the percentages are telling him with respect to offensive tendencies.

If the offense is showing run tendency, he will typically make a defensive call that is geared to stopping the run and it likely includes some type of run blitz. If the offense is showing pass tendency, the defensive call will be geared to defend the pass (and likely includes some form of pass pressure). But in either case, the pre-snap alignment of the players will be balanced to the run and the pass, allowing them to defend both.

Let’s explore pass pressures a little further as it relates to Bud Foster’s system.

Remember that Bud Foster’s philosophy is to stop the run and put pressure on the offense. Pressure against the pass includes a mix of man and zone blitzes. As mentioned earlier, man pressures are more risky, but Bud Foster will “bring the house” on occasion, particularly when the offense empties the backfield. His objective against an empty set is to bring maximum pressure, play Cover-0 (more on that in a bit) and force the QB to get rid of the ball very quickly.

Zone pressures are less risky and they make it much more difficult for offenses to use built-in hot routes because the blitzing defender typically isn’t responsible for covering the hot receiver. Instead, using zone pressures, the Hokies will blitz with two additional defenders and rotate into zone coverage behind the blitz forcing the QB to find open areas in zones versus simply reading the blitz and throwing to the hot receiver.

The two blitzing defenders will be some combination of the linebackers, corners, or free safety/rover. Using personnel and formation tendencies, Foster will localize the blitz pressure to one side of the formation or the other, based on the number of blockers available on each side of the ball and the type of protection scheme the offense has shown on film from that formation and personnel group. The offense must determine where the pressure is coming from and correctly adjust the protection scheme to account for it. If Foster’s zone pressure call is to bring four defenders (2 DL + 2 blitzers) on the same side of the ball, then the protection scheme must have four blockers on that side; otherwise, one of the Hokie defenders will come unblocked.

This is a classic case of how disguising directional pressure goes hand in hand with disguising coverage. Without a clear pre-snap read, it is difficult for the offense to determine who is blitzing (and where it is coming from) and how many are dropping into zone coverage. Without a good read, there is a high probability that the protections will not be adjusted correctly and Coach Foster will get exactly what he is looking for – more defenders rushing from one side of the ball than the offense can block. It’s easy to see that the advantage goes to Bud Foster and his defense.

This is just one example of how a defensive coordinator can use zone pressures to remain aggressive while playing “safe” in coverage.

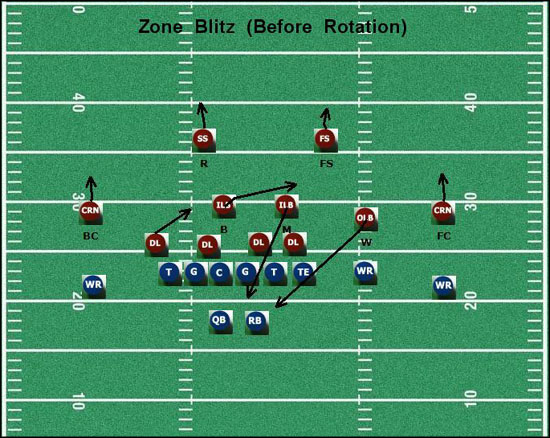

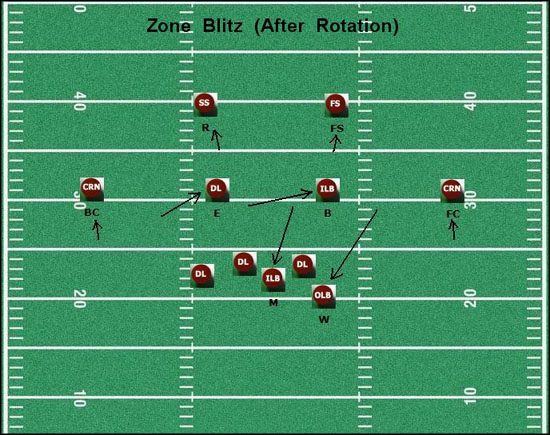

Other examples of zone pressures include blitzing additional defenders on one side of the field while dropping one of the defensive linemen into an underneath zone coverage on the other side of the field. There are many variations of this type of zone blitz, but most are based on the idea of getting additional directional pressure on the QB while still having six defenders back in zone coverage.

This is the classic variation of the zone blitz that is familiar to many fans and used by almost every defense these days. By using this type of “player exchange”, the defense can direct pressure with two additional rushers, but protect itself in coverage by exchanging one of those blitzers with a defensive lineman on the other side.

Why did this type of zone blitz become so popular among the current generation of defensive schemes? Offenses used to counter traditional blitzes simply by keeping more people in to block (max protection). Over time, instead of always countering blitzes with max protection, quarterbacks and receivers were coached to adjust the planned pass route when they read blitz. This is called a sight adjustment and the idea is for the receiver to adjust his route and instead run to the vacated spot (left open by the blitzing defender).

The zone blitz with a player exchange takes that option away because the spot really isn’t vacated. Instead, the coverage is rolled directly towards the vacated spot with the defensive lineman dropping out on the other side. If the quarterback and receiver misread the pressure and coverage, then it can be an easy pick for the defense.

Bud Foster is aggressive using his defensive linemen in this manner. He will drop any of the four into coverage, sometimes even dropping one of the defensive tackles into popular passing lanes utilized by offenses in their quick passing game. Watch for that this season….don’t be surprised to see Barry Booker, Carlton Powell or even “Big Country” Kory Robertson get a pick!

Coverage Shells

The defense just came up with a big interception. The television broadcast shows several different replays with the analyst using his trusty telestrator to show what and how it happened. “That was a great call by the defense. They showed Cover-2, but it wasn’t. The quarterback never saw the safety in the middle of the field…..”.

Then it’s off to the next play without further explanation. Frustrating isn’t it?

We will complete this part of the series with an overview of the various pass coverage shells. There are many variations, but for the purposes of this article, we will cover the five or six most common pass coverages utilized by the majority of college and pro defenses today.

The basic terminology is “Cover-X” where the “X” defines the number of deep pass defenders associated with that particular coverage. For example, “Cover-2” has two deep pass defenders; “Cover-3” has three deep pass defenders, and so on.

Let’s go through each one in a little more detail….

Cover-0

This one sounds a bit dangerous because, as the name implies, the defense has no deep defenders in this coverage. This is the classic man-to-man coverage with a full blitz. In other words, a single defender matches up with each eligible receiver and everybody else on defense makes a beeline to the QB. Every pass defender is “left alone on an island” without any help.

As mentioned earlier, the Hokies will often go with Cover-0 when the offense shows an empty formation (i.e. the QB is alone in the backfield).

This approach to an empty set tends to get pressure on the QB very quickly and forces him to get rid of the ball before he can get set. That’s a good tradeoff for the defense since the defenders generally are not required to “stay on an island” very long.

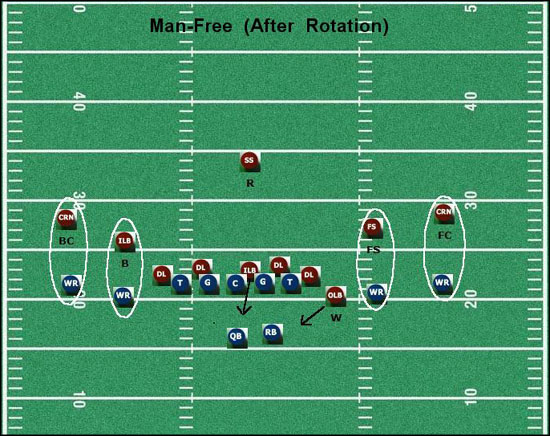

Cover-1

This coverage often is referred to as “man free” coverage. In Cover-1, there is a single defender in deep coverage providing help against deep pass routes. This is generally a safety that is aligned in the deep middle prior to the snap. Like Cover-0, Cover-1 is base man-to-man coverage with five defenders matched-up in man coverage against the five eligible receivers. With one additional defender providing deep help, Cover-1 has six defenders in pass coverage, leaving five defenders to rush the QB.

If the offense chooses to keep eligible receivers in as part of the protection scheme, then an equal number of defenders can blitz the QB. In other words, in Cover-1, the defense can always rush the same number of defenders as the offense has in their protection scheme. With a five man protection, the defense can rush five; with a six man protection, the defense can rush six, and so on.

That’s the upside of Cover-1. With great athletes at corner and safety, a Cover-1 defense can be suffocating. Cover-1 was a favorite of the Hokies back in the days of the 8-man fronts. The defense blitzed on nearly every play with man-to-man coverage behind it. The 8-man front meant eight defenders inside the box and three defenders outside the box – the two corners and one safety – a perfect pre-snap look for the Cover-1.

The downside of the Cover-1 is the risk associated with man-to-man coverage with only one defender to provide deep help. This is particularly true if any of the receivers have match-up advantages against the corners or the linebackers. If the offense can create enough time to send multiple receivers deep, then the defense can be really stretched and big plays are possible.

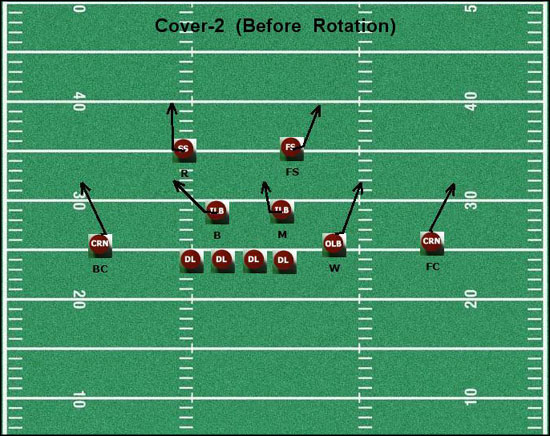

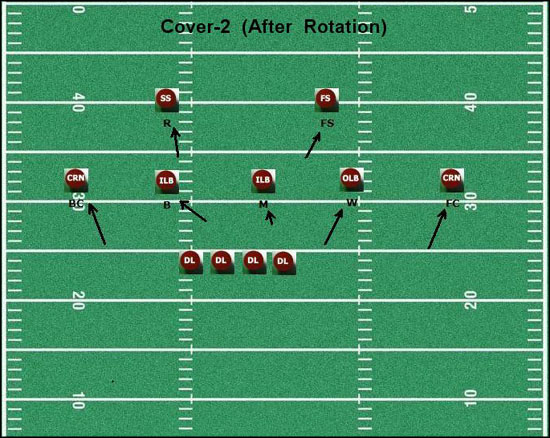

Cover-2

The most discussed and most utilized zone coverage in football is the Cover-2. As the name implies, the Cover-2 is a two deep coverage and is generally implemented with the two safeties back as deep defenders.

The concepts of a two deep coverage have been around since zone defenses were first invented. The primary elements of the Cover-2 remain based in those original concepts and include refinements that are well suited for defending the short passing game used by so many offenses today.

The base Cover-2 is a pure zone defense with seven defenders back in pass coverage. The field is divided into two deep zones and five underneath zones. The two safeties are the deep defenders and they are responsible for the deep halves. The five underneath defenders are the three linebackers and two cornerbacks and they each are responsible for one of the five underneath zone areas.

The advantages of the Cover-2 is that it gets five pass defenders in the areas that offenses look to exploit in the short passing game (popularized over the years with the evolution of the so-called “west coast offense”). It brings the corners up to the line of scrimmage where they can get bumps on the receivers to disrupt routes and the timing of the passing game.

The pressure points of Cover-2 are on the deep safeties – they have a lot of ground to cover, particularly in the deep sideline areas behind the cornerbacks. To minimize this exposure, it is important for the corners to bump the outside receivers off the snap and force them to take their route towards the inside. If they get outside the corners, then the deep sideline routes are fertile ground for the offense to exploit.

Because the safeties have so much ground the cover, the corners also have to take the outside routes as deep as possible to help close those weaknesses in the deep outside of the coverage. Offenses will counter by pressuring the corners to make decisions using high-low routes. One very popular high-low combination is to send an outside receiver on a post-corner route and have the tight end release and attack the outside flat underneath. This puts pressure on the corner to decide how deep to defend the wide receiver on the post corner before coming off to defend the tight end sliding out in the flat. This is an example of the importance of “pattern read” and how everyone in pass defense must be cognizant of what all the receivers are doing with their pass routes.

There are many variations of the Cover-2. One variant is called Cover-2 Man Under (sometimes called 2 Man Under or Cover-2 Man). In this defense, the two safeties are still in zone and remain responsible for the deep halves of the field, but the five underneath defenders play man-to-man coverage against the five eligible receivers. This can be a very effective change-up for the defense because the pre-snap Cover-2 Man looks exactly the same as the base Cover-2. The offense is expecting to use their zone plays to attack the five underneath defenders, but instead the receivers get locked up in man-to-man coverage.

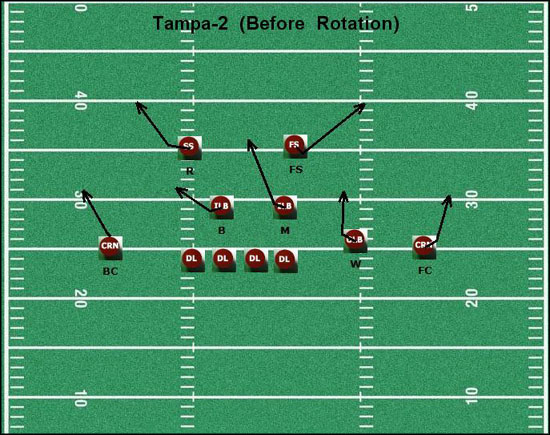

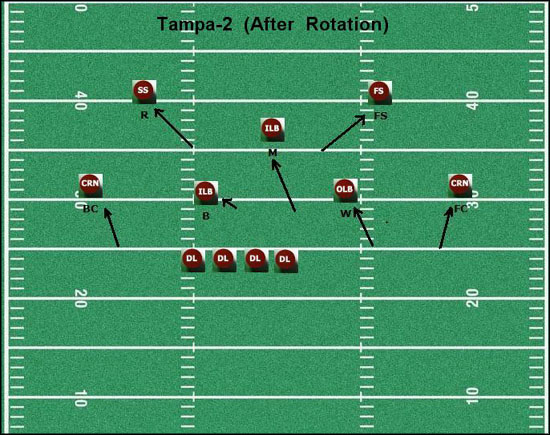

Tampa-2

Another variation of the Cover-2 is the “Tampa-2” defense made famous several years ago in the NFL by the Tampa Bay Buccaneers. The Tampa-2 has been described many ways, but for our purposes, we will focus on how it differs from the base Cover-2 in terms of pass defense.

Remember that one of the weaknesses of the base Cover-2 is that the two safeties have a lot of ground to cover – each safety has to defend one half of the field. The deep sideline areas are the most difficult to defend because each safety has a long way to go to get there.

The Tampa-2 adjusts for that by shading each safety closer to the sideline, reducing the ground they have to cover in order to defend those deep sideline areas of the field. This exposes the deep middle and the Tampa-2 accounts for that by requiring the middle linebacker to take a much deeper drop in pass coverage. The result is 2-deep coverage that is pseudo 3-deep coverage.

The primary advantage of this coverage is that it minimizes the exposure to the deep outside because the safeties are shaded toward those outside areas. It also takes some pressure off the corners in defending those high-low routes that offenses like to use to attack the base Cover-2. And with great athletes at the linebacker positions, it is also more difficult for offenses to attack the seams because of the deeper drops.

The weaknesses of the Tampa-2 start with the middle linebacker. For it to work effectively, the middle linebacker has to be not only a good athlete, but also an intelligent player that can read keys correctly and react quickly to what the offense is doing.

Offenses will try to use play-action in order to freeze the middle linebacker and get a tight end or slot receiver behind him down the middle of the field. With the safeties shaded towards the sideline, the offense can hit for a big play if an inside receiver can release cleanly and get behind the middle linebacker immediately after the snap. Tampa-2 style defenses will counter by ensuring that all inside receivers (tight ends, slot receivers, etc) get bumped off the line of scrimmage in order to prevent a clean release down the middle of the field. This disruption off the line of scrimmage delays the receivers’ ability to get down the field and buys time for the middle linebacker to recover from play action and take his deep drop before an inside receiver can get behind him.

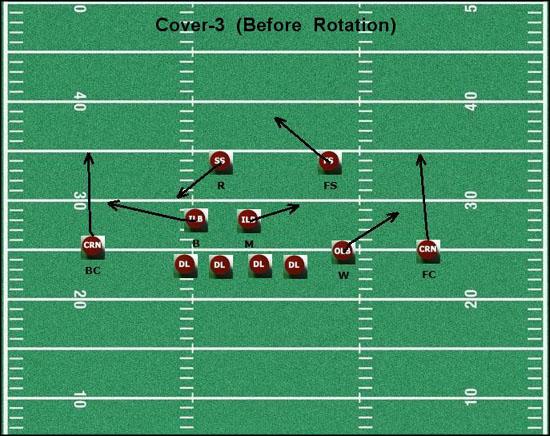

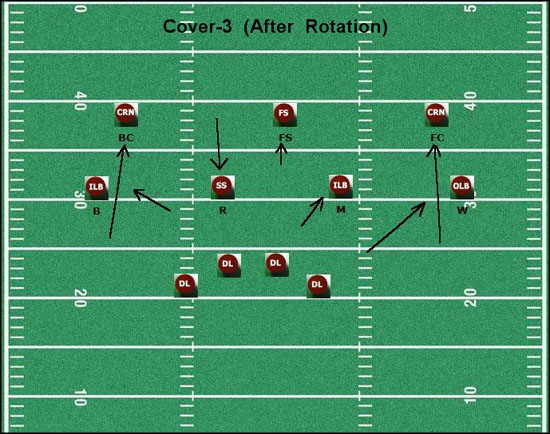

Cover-3

Continuing the trend, Cover-3 is a zone defense with three deep defenders and four underneath defenders. The three deep defenders are usually the two cornerbacks and one safety, each dividing the deep part of the field into thirds. The four underneath defenders are the three linebackers and the remaining safety, each dividing the underneath part of the field into fourths.

The Cover-3 is particularly effective against the deep passing game because there are three strong pass defenders covering the deep areas of the field. It is a popular coverage call in 3rd and long down/distance situations.

Cover-3 is also strong in other down/distance situations because the defense can walk up one of the safeties (8-in-the-box) and still get to 3-deep coverage simply by dropping out the two corners. This type of pre-snap look is confusing to the offense because with 8-in-the-box, the defense is strong against the run and can easily play man-free coverage (Cover-1) or zone coverage (Cover-3). Both show a deep safety in the middle of the field, so the quarterback cannot rely on the pre-snap position of that safety to determine which pass coverage the defense is in.

The primary weakness of the Cover-3 is the flat areas in underneath coverage. Since the corners drop out into deep coverage, the pressure is on the outside linebackers to cover the flats. Offenses that see Cover-3 will generally attack the flat areas and look for the receivers to turn it up the sideline.

The Cover-3 is a popular pass coverage call for the Tech defense. Because he likes to get the Rover up close to the line of scrimmage in certain situations, Bud Foster can show Cover-3 against the run or the pass. And because he has a guy like Xavier Adibi at Backer and hybrid type athletes at Whip and Rover, the Hokies can defend the underneath flat areas with excellent athletes that are strong in pass coverage.

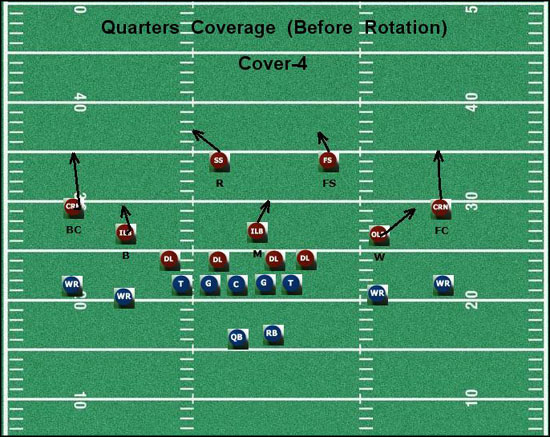

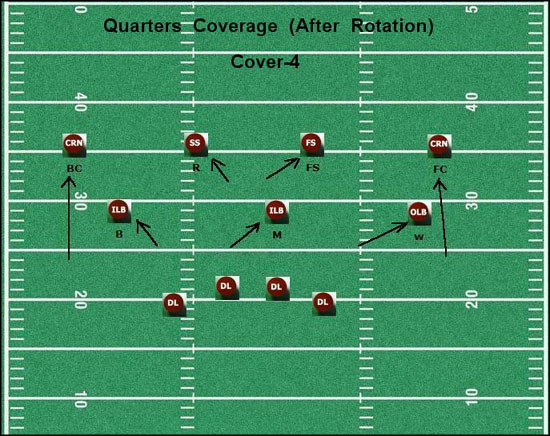

Cover-4

Finally, there is Cover-4 or “quarters” coverage. As the name implies, Cover-4 is a zone defense with four deep defenders and three underneath defenders. The four deep defenders are the two corners and two safeties. The linebackers are three underneath defenders.

Cover-4 is a very strong defense against deeper passes and it is used regularly in long yardage situations. It is very difficult for an offense to complete a deep pass against a defense that has both corners and both safeties aligned in coverage to specifically defend against those types of passes.

Cover-4 is used often as a “prevent defense” in very long down/distance situations or at the end of the half/end of the game when the offense is behind and needs to score quickly. It takes the long play out of the equation and forces the offense to throw short.

On occasion, defenses will substitute an additional defensive back for one of the defensive linemen in order to get four pass defenders in underneath coverage. Many fans dislike this type of Cover-4 prevent defense even though it gets eight pass defenders in coverage against five receivers. The defense rushes only three and often has difficulty getting pressure on the quarterback. Sometimes (and far too often for many fans), very good quarterbacks are able to pick apart the defense, manage the clock, and methodically work their way down the field for the winning score.

Conclusion

I rarely watch the ball when Tech is on defense. I usually look at how the linebackers and defensive backs are aligned and then watch for any movement or shifting as the play is about to unfold. I’ll then use the reaction of the defense to find the ball after the play has started. Over many years of doing this, I have learned a lot about the Hokie defense, but I have really only scratched the surface. For me, it is fascinating to watch Bud Foster’s system at work and I always look forward to learning something new each and every game.

Try it if you can….I think you will find watching a game in this way to be a very different experience. And when you see the two cornerbacks backing off the line of scrimmage just before the snap, you will know that the coverage call was most likely Cover-3 or Cover-4 zone. Or was it actually Cover-1?

I hope you have found this series to be helpful and informative. I am a big fan of Bud Foster and his defense, so I certainly have enjoyed writing it.

After several trying months, the Hokie Nation is ready for some football. See you all in Blacksburg on Sept 1. I am sure it is going to be a very memorable experience.

Note: This material was not reviewed or edited by any member of the Virginia Tech football coaching staff and is the author’s own personal observations and interpretations of the Virginia Tech defensive scheme and philosophy.

Tech Sideline is Presented By: