Click here to access all three parts of the Hokie Defense series by Raleigh Hokie

Note: This is the second installment of a three part series about Virginia Tech’s nationally renowned defense. Part 1 covered some basic concepts, including a description for each defensive position.

Note: This is the second installment of a three part series about Virginia Tech’s nationally renowned defense. Part 1 covered some basic concepts, including a description for each defensive position.

Ok. So we have a basic definition for each of the eleven puzzle pieces. How do those pieces fit together and how do they work collectively to form one of college football’s best defenses?

In this installment of the series, we will cover the general concepts of Bud Foster’s defensive scheme, including how offensive personnel and formation impact defensive alignments and responsibilities. We will review the scheme adjustments that were made following the 2003 season and the impact they have had. And finally, we will take a look at how all of the calls and adjustments for each play are communicated from the coaches to the players.

Basics of the Scheme

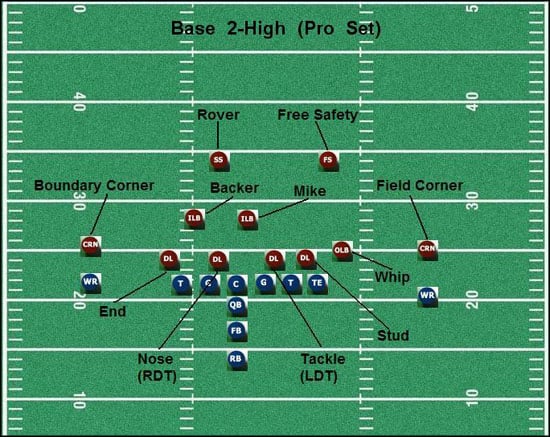

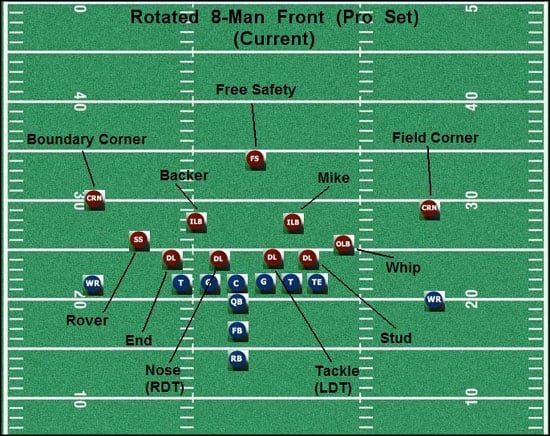

The Hokies play a base 4-3-4 defense, meaning that there are four defensive linemen, three linebackers and four defensive backs in the base set. In certain situations, without changing the personnel, the Hokies will play an “8-man front,” with four defensive linemen, four linebackers, and three defensive backs (4-4-3 alignment). The adjustment from one set to the other depends on the alignment of the Rover. In the 4-3-4 base set, the Rover aligns as a defensive back, specifically as one of the two safeties. In an 8-man front, the Rover will rotate up closer to the line of scrimmage and align as the fourth linebacker.

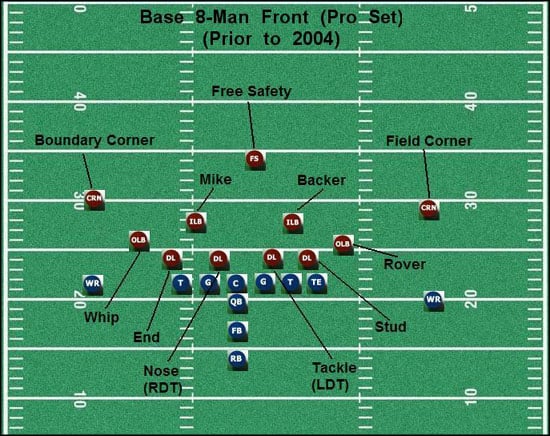

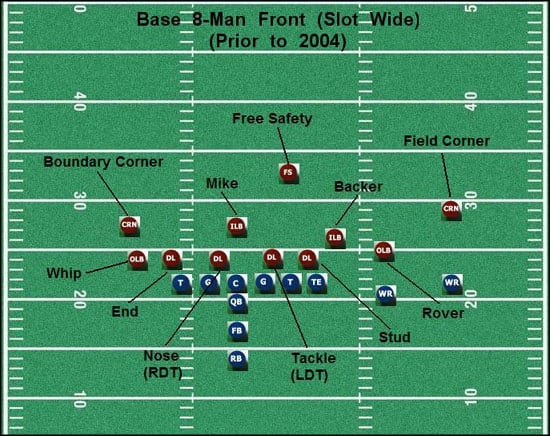

Prior to 2004, the Hokies were primarily an 8-man front defense and everything worked off of that. The Hokies used a base 8-man front the majority of the time. In obvious passing situations, the Hokies would shift to a base 4-3-4 look by dropping the Whip as the second safety.

The players also aligned differently. Prior to 2004, the alignment of the linebackers and safeties was based more on the strong side / weak side of the offensive formation. The Backer and Rover were strong side players, so they would usually align to the strong side of the formation. The Whip and Free Safety were more weak side players, so they would usually align to the weak side of the formation. The DE’s aligned much like they do today with the Stud always to the wide side and the End always to the boundary.

Against an 8-man front, it was difficult for offenses to establish the run because there was generally one defender unaccounted for in the blocking scheme. And stopping the run was (and still is) the #1 goal of Bud Foster’s defense.

It was a very clever scheme because it could be adjusted to a pass oriented defense by slipping the two outside linebackers (the Whip and Rover) into coverage as defensive backs. In other words, without changing the base personnel, it was a scheme that could adjust play to play from a run stopping 8-in-the-box set to a strong pass stopping set with five defensive backs (Whip, Rover, Field Corner, Boundary Corner, Free Safety).

And then there was all the blitzing. It was difficult for offenses to determine how many were blitzing and how many were dropping into coverage. This aggressive nature of the defense led to years with incredible tackles-for-loss numbers.

But after several seasons of getting pounded into the turf by the Tech defense, teams began to spread things out and use more 3-4 wide receiver formations to isolate certain match-ups. With those 3-4 wide formations, they could isolate a quick, speedy receiver in man coverage against Tech’s Backer and Rover to the strong side of the formation. That was generally the wide side of the field as well, so the Backer or Rover had to cover a faster, quicker player out in open space.

On the other side, teams could get favorable running game match-ups by running to the boundary. Containment often fell onto the shoulders of the Whip LB, a hybrid player that was part linebacker and part safety. For that reason, some teams found success by running weak side out of those spread formations.

Other teams began to use a lot of quick passes and/or maximum protection blocking schemes to counter Tech’s blitz tendencies. By keeping the tight ends and running backs in to block, offenses could buy additional time to go to their wide receivers running down the field against single, man-to-man coverage. With the quick passing game made popular through the concepts of the west coast offense, offenses could beat blitzes by going with quick passes to hot receivers and allowing them to use their athletic abilities to gain significant yardage after the catch (YAC).

In combination, these adjustments resulted in more big plays against the Tech defense, both in the running game as well as the passing game.

Time for Adjustments

To counter these offensive trends, Bud Foster made some adjustments to the base defense after the 2003 season. The changes were not major in terms of philosophy and were primarily related to base sets, player alignment and the responsibilities of the Whip and Rover positions.

In terms of base sets, the Hokies transitioned from being a heavy 8-man front defense to a 4-3-4 base set characterized by two deep safeties. From this base set, the Hokies can play any number of man and zone coverages while still getting to an 8-man front on any play by rotating the Rover up closer to the line of scrimmage just prior to the snap.

This “4-3, 2-high safety” base set gets the defense in a much better pre-snap position to defend offenses that like to use a lot of spread or 3-4 wide formations. The 8-man front, aggressive blitzing style of defense often forced the Hokies to play man coverage across the board with little or no deep help. As mentioned earlier, that led to man-to-man match-ups of a linebacker or Rover against that third and fourth wide receiver. If the blitz didn’t get to the QB quickly, then the defense was at risk for a big play.

With a 2-high safety base set, the Hokies can play a lot of different zone coverages (while still playing man coverage when they want), preventing offenses from dictating match-ups with their personnel groups and formations.

The result of these adjustments is a scheme that has proven to be more effective against the current trend of spread formation, passing-oriented offenses.

The scheme is also simpler to execute because the players are aligned based on ball position, rather than on the strength of the offensive formation. They know where to be and they know how to adjust more quickly to formation shifts and motion. This allows the players to react instinctively and play with more confidence. As the coaches like to say, “it is important that their minds do not tie up their feet”.

And that is a key aspect of playing great defense, especially when the system relies heavily on speed, quickness and pursuit.

Communication is Vital

Speaking of personnel groups and formations, have you ever wondered what Bud Foster and Charley Wiles are doing with all the hand signals between plays? What about that sign board with numbers like “21” or “11”? What does that mean?

There are a number of factors that the coaches consider when setting the defense from play to play. Some of the biggies are game situation, down and distance, ball position, and offensive personnel.

Game situation includes things like score, wind / weather conditions and time remaining on the clock.

Down and distance is fairly obvious. The defensive calls will be different on 2nd and three versus 3rd and nine.

Ball position refers to the position of the ball relative to the hash marks. Many defenses set the alignment of their players based on sides of the ball (ie, left and right) or formation strength (ie, which side the TE is on).

As covered in Part 1, the Tech defense aligns based on ball position relative to the hash marks. The wide side is called the “field” and the short side is called the “boundary”. In terms of positions, the Stud, Whip, Mike, Field Corner and Free Safety always align toward the wide side of the field. Likewise, the End, Backer, Boundary Corner, and Rover always align toward the short side of the field.

The offensive personnel or personnel group is the makeup of offensive skill positions for any given play. That sign board on the sideline is a tool that identifies the offensive personnel group. The first number reflects the number of running backs and the second number reflects the number of tight ends. The number of wide receivers is derived from the combination of those two numbers. For example, a “21” personnel group is two running backs, one tight end, and two wide receivers. An “11” personnel group is one running back, one tight end, and three wide receivers. This is very important information that is communicated by the coaches in the booth to the coaches on the sideline. A student manager then uses the sign board to communicate the personnel group to the players on the field.

Clear as mud right? Maybe an example would work here.

Simple as 1-2-3….Or Not

Let’s go through the sequence that takes place in the 20-30 seconds between the end of one play and the next snap. Several things are known at the end of the first play — game situation, down and distance and ball position.

The offense makes the next move by setting their personnel group — for this example, they have just removed one of their two running backs and sent in a second tight end. One of Tech’s defensive coaches in the booth communicates the ball position, down/distance and personnel group to the coaches on the sideline. Using a series of hand signals, Bud Foster communicates the defensive call (set, blitz call, passing strength, coverage, etc) to the players on the field. Charley Wiles communicates the front call to the defensive line (stunt calls, etc). A student manager signals the personnel group (“12” in this example) via the sign board. The defensive call in combination with the personnel group establishes the specific pass coverage responsibilities for the defense.

That gets us to the pre-snap look for second down. At that point, the players on the field know the down/distance and the front, pressure, and coverage calls. They know on which side to align based on ball position. In addition, they know the personnel group and the pre-snap formation. From the formation, they know the passing strength of the offense and based on that they will slide their respective alignments accordingly (still within the basic alignments defined by ball position).

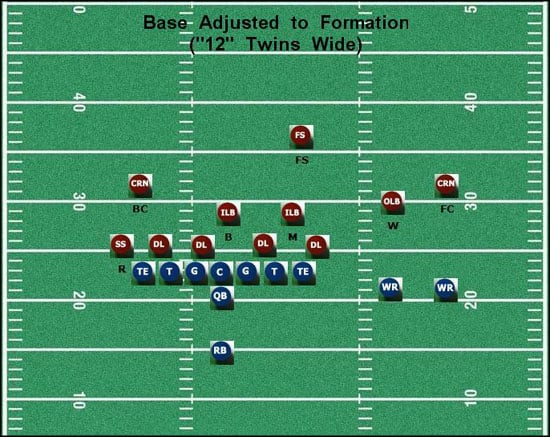

For this example, here is a pre-snap diagram of a likely defensive set against a “12” personnel group (one RB, two TEs, two WRs). The formation is twins wide, so the passing strength is heavy to the wide side of the field.

The defense slides their individual alignments based on that personnel group and passing strength. Note that with no receivers split to the boundary, the Rover will rotate up to the line of scrimmage and align as a linebacker on the boundary side. The Whip slides over in a defensive back alignment over the inside receiver. The result is a 4-3 base that follows the general rules of alignment with the players sliding and rotating based on personnel group and passing strength. Note with that pre-snap look, it would be difficult for the QB to read the coverage (is it man or is it zone?).

A lot can still happen from that base pre-snap state, including shifts, motion, and checks/audibles by the offense. The offense uses those techniques to get a better read on what the defense may be doing. Sometimes shifts and motion will force the defense to tip its hand. Tech makes that difficult because there is a “hand off” of responsibilities as the offense shifts or motions out from one passing strength to another. By handing off in this way, the defenders do not tip the coverage.

For example, a corner will not follow a motioning receiver across the field, even if it is man coverage. Instead, the coverage responsibility for that motioning receiver will be handed off to a defender already aligned on the other side of the field.

In addition to these types of coverage adjustments, there may be front and pressure adjustments made by the defense as well.

All of those adjustments are made in real time by the players on the field. Normally, it will be one of the linebackers that will communicate any adjustments to the defensive front call or blitz call. The free safety is responsible for coverage adjustments and making sure that everyone is lined up properly.

From the coaches in the booth, to the coaches on the sideline, to the players on the field, to the pre-snap adjustments; that is a lot of communication and it is pretty much non-stop in those 20-30 seconds between each play.

From a fan’s perspective, it is easy to see that football is very challenging physically — it’s arguably the most physical of any sport in the world. The players have to be extremely strong, tough and physical and they have to enjoy full force contact against other guys that are just as big, just as strong, and just as tough. It is definitely not a finesse sport.

What may not be as obvious is that football is equally challenging mentally. Everybody has to be on the same page and know their assignments within the structure of the defense. And then they all have to stay on the same page through a series of on-going adjustments just before the ball is snapped. One breakdown or miscommunication and the other team could be in the end zone.

So, every player has to know exactly where to be, exactly what to do, and exactly where to go before running with reckless abandon into a full speed collision. Sounds like fun doesn’t it?

Back to our play example. The offense goes through its gyrations to get a better pre-snap read and the defense adjusts accordingly. Finally, the ball is snapped and the play runs to completion, most likely in five seconds or less. And based on the history of Bud Foster’s defenses, it’s likely that the play is stuffed.

The whistle blows, the players un-pile and the cycle starts again.

That is a lot for the players to process isn’t it? Remember that what I am describing in this series is at the 5,000 foot level. There are a ton of details that are critical for the defense to execute properly. Body positioning, angle of alignment, depth of alignment, how to come off the snap (use of hands, proper footwork, etc), reading each individual key, reacting properly to those keys, proper pursuit angle, tackling technique….that is just a short list of things that the players must focus on correctly as a unit for the defense to be successful on any given play.

It is fascinating stuff and beautiful to watch when it produces the type of results that we have seen over the years from Bud Foster’s bunch.

Whip and Rover Adjustments

Before I wrap up this part of the series, I want to get back to the adjustments made after the 2003 season. At the time, there was a lot of discussion about the changes, both from the coaches directly and from others close to the program. Most of the comments were centered on the adjustments to the Whip and Rover positions, so I wanted to revisit that and clarify some points in those areas.

As mentioned earlier in this article, the coaches decided to make these adjustments because offenses had schemed some things to specifically attack Tech’s 8-man front base defense with more 3-4 wide receiver sets and more spread formations. At the time, the Whip and Rover were described as hybrid players that had combination linebacker/defensive back responsibilities.

The Whip was a weak side outside linebacker in the base 8-man front and he was a weak side safety in the 2-deep safety set (base used regularly in passing situations). The Rover was a strong side outside linebacker in the 8-man front that would slide out as an additional corner / defensive back against 3-4 wide receiver formations.

The primary adjustments were to go to a base 2-high safety set (as discussed earlier), with the Whip up as a linebacker full time and the Rover back as a safety in most alignments. This is a more “traditional” 4-3 defensive set that allows the Hokies to get to all of their fronts, pressures and coverages from the same single base set.

It also put the Whip and Rover in better positions to be successful. While they are both still hybrid type players, their responsibilities are more confined. This is especially true for the Whip LB, who no longer drops back as a deep safety in any situation. Keeping the Whip closer to the line of scrimmage allows him to play more like a true linebacker, which helped an athlete like James Anderson flourish at the position.

Going into last season, there was legitimate concern about Brenden Hill playing a position that had become more defined as a linebacker, but he proved that a player of his physical abilities could be productive as a Whip as well if he handled his assignments correctly. The coaches helped by putting him in positions where he could be successful. Instead of taking on offensive linemen as a run stuffing linebacker, he was used more to play containment or run blitz off the edge. The transition from James Anderson to Brenden Hill without skipping a beat showed two things — (1) the coaches know how to put different type players in a position to succeed and (2) while better defined to defend against today’s offensive systems, the Whip still is a hybrid position.

Likewise, by no longer asking the Rover to man up against speedy slot receivers to the wide side of the field allows linebacker / safety type athletes like Aaron Rouse to be successful at that position. Without the post-2003 adjustments, there would have been many plays where Rouse would have been isolated in man coverage against the slot receiver. That would have been tough duty for a guy like Rouse, who was much better suited for the current responsibilities assigned to the Rover — (1) back as a deep safety to the boundary side or (2) up at the line of scrimmage as an outside linebacker playing boundary run containment or picking up a tight end in man coverage.

The results of these adjustments speak for themselves. Since the scheme was “tweaked,” the Tech defense has finished ranked #4, #1, and #1 in the nation in total defense.

Not bad eh?

Next Up: All of those confusing pass coverages. You have heard the laundry list of coverage terms, but what do they mean? What is a Cover-2 and how does it differ from a Cover-3? What is a zone blitz? How does pressure relate to coverage?

Part 3 and the final installment of this series will be dedicated to pressure concepts and the more popular pass coverage sets used by Virginia Tech and many other teams around college and professional football.

Tech Sideline is Presented By: